College and Career Pathways Leadership Guide

Site Leaders

Coherent Redesign: Reassessing the vision and mission of the school redefines the priority of pathways, and allows teacher leaders to balance the needs of their own programs with those of the school as a whole.  What should change, why it should change, and how that affects the site are important school-wide conversations that lay the groundwork for all staff to understand and support pathway development. Master scheduling processes, teacher hiring and assignment, new student recruitment, and other routines can be rife with conflict when each lead is fighting for their own program, department or pathway. By working with all departmental, pathway and program heads to form a community of practice with a common vision and mission for the school, school leaders can help develop the capacity to manage that conflict productively and negotiate solutions that put student learning first.

What should change, why it should change, and how that affects the site are important school-wide conversations that lay the groundwork for all staff to understand and support pathway development. Master scheduling processes, teacher hiring and assignment, new student recruitment, and other routines can be rife with conflict when each lead is fighting for their own program, department or pathway. By working with all departmental, pathway and program heads to form a community of practice with a common vision and mission for the school, school leaders can help develop the capacity to manage that conflict productively and negotiate solutions that put student learning first.

A school’s ability to function as a unified organization, rather than as individual practitioners or separate programs, is a necessary condition for engaging in continuous improvement. Diversity can be a great strength in schools with multiple pathways, but should co-exist with interdependence and collaboration to ensure that the whole school is in a transformative process. A site-wide leadership team committed to continuous improvement can develop professional working agreements, like these from Oakland High School, that model a professional approach to school transformation. The Internal Coherence Assessment and Protocol & Developmental Frameworks can be used to assess and improve a school’s ability to harness the collective resources of the organization to achieve collective goals.

Inclusive Site Leadership Structures: Pathway leads work closely with site administrators to organize what their particular pathway needs, which often conflicts with other priorities at the site. Unless inclusive site leadership structures have been built, pathway leads may not even know what the conflicts are, or how to contribute to workable solutions. When pathway lead teachers engage with other site leaders in determining priorities, they can integrate their pathways’ vision into that of the school at large, and facilitate the development of the Linked Learning approach school-wide. Pathway leaders can participate in determining schoolwide professional development priorities, on the master schedule team, the English Language Advisory Committee, the school Site Council, as teacher’s union representatives, and on other leadership bodies.

Building supportive relationships between administrators and pathway teacher leaders entails establishing new norms and structures, and explicitly reviewing responsibilities. In the process of transitioning to wall-to-wall pathways, Oakland High School developed this graphic depiction of working relationships between key support staff and administrative units. Another graphic describing an inclusive site leadership structure emphasizing teacher leadership at a large comprehensive high school with multiple pathways is available HERE.

New pathways: Selecting teacher leadership for a new pathway is more difficult, as a team must be created, and leadership develops over the course of the team’s work together. A planning year allows leadership relationships to emerge. After explaining the idea of the pathway, and the timeline, support and resources that will be available, interested teachers can be identified, and a team can be developed. A valuable resource for that work is the CCASN Planning Guide for Career Academies.

Selection process: In either case, a processes that allows teams to nominate their own leaders is far more effective than the appointment of teacher-leaders by administrators. If teacher leadership positions are part of a union contract, the union may play a role in soliciting nominations and conducting annual elections. While such elections do not have to be binding, the process ensures that leaders are accountable and legitimate, which increases their effectiveness. An annual process of leadership selection should review both the pathway lead responsibilities, and the many areas in which pathway teachers are expected to share leadership responsibilities.

Pathway Leaders’ Work: Lead teachers in pathway teams organize discussions among team teachers and contribute to site-wide discussions about vision and mission, pathway student outcomes, pathway course sequences, and essential student support structures. They create forums to involve parents, community, industry and post-secondary partners, and they work closely with site administrators to ensure that pathway plans fit well with the site vision and mission. They provide essential instructional leadership, modeling innovative and collaborative instructional strategies that integrate academic and career technical content, and promoting such strategies within their team.

Teacher Team Assignment: The context in which the pathway is developing determines many of the challenges in forming teacher teams, but a few critical principles apply to team formation in any context:

- Teacher interest in the particular sector and/or willingness to collaborate with the teacher team to shift instruction to connect to the career field is crucial.

- A transparent process needs to be in place to educate teachers about the nature of the different pathway teams, and to solicit teacher preference for assignment. See this sample form for soliciting teacher input.

- An inclusive site leadership body should help define the principles for resolving conflicts in teacher assignment in a transparent and equitable manner.

- Equitable student access to high quality teaching is a key outcome for the teacher assignment process.

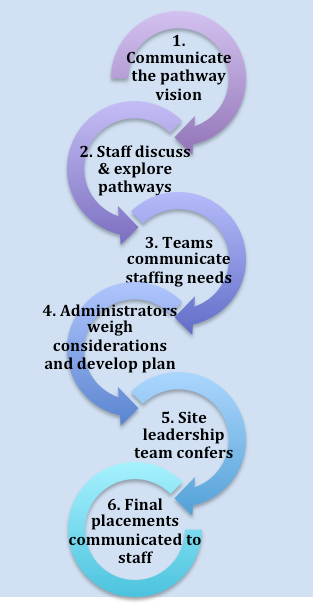

An exemplary step-by-step process for involving teacher leaders in assigning teachers to pathway teams is outlined in the graphic on the right, and available here.

Coherent Pathway Design: Many of the decisions that individual pathways make affect the school at large; from how work based learning occurs, to the size of the pathway, to the courses students are able to access when they are in a pathway. Pathway programs of study are part of a complicated master schedule, which organizes who teaches and who learns what, when and where. The calendar of the master schedule is very different from the academic calendar, and organizing it to address the needs of both teachers and students can be very challenging. When teacher leaders become partners in developing the master schedule, they participate in developing its priorities and addressing potential conflicts. This process develops collective expertise, and the team’s ability to negotiate and problem solve. A valuable resource for this work is the CCASN Master Schedule Guide, available here.

Equitable Pathway Design: Disparities in educational outcomes typify U.S. high schools. The critical challenge facing site leaders is to build pathways that offer equitable access to educational opportunities for all students. The sixth year evaluation of the Linked Learning District Initiative (Warner 1) identifies three components to ensuring equity in pathway development: equitable access to pathways, representative enrollment, and student persistence. We would add a caution that pathway designs must also offer access to equitable post-secondary options.

Key discussions: How pathways are organized affects all students at the school. Because schools have consistently underserved specific student populations, it is essential to engage in discussions with the site leadership team about the principles of equitable pathway design. Some important questions for discussion include:

- How are students recruited to the pathways? Is enrollment open? Is recruitment centralized?

- Are all pathways’ recruitment materials equally impressive? Is information on pathway options widely available in the languages students and their families speak?

- Are students and families able to make informed choices based on student interest in a career field? Can students experience pathways through visits, middle school or summer bridge programs prior to making their selections?

- Are English Language Learners and Special Education students able to participate in pathways?

- Are there criteria for entrance into some pathways that prevent equitable access?

- Are student supports in place to ensure that students from all backgrounds have the opportunity to excel in each pathway?

- Do all pathway provide students access to a CTE technical core sequence, the a-g UC/CSU entrance requirements, and opportunities for advanced coursework?

- Are disparities in the student populations served by pathways addressed conscientiously?

- Are there equitable procedures to ensure that most students can attend their first or second choice of pathways?

- Given the tendency of choice-based systems to recreate inequitable divisions, how can recruitment and placement policies balance choice and equity concerns?

- Are procedures for changing pathways clearly communicated and equitably applied?

In their study of Linked Learning districts, Warner et. al. also note that when pathway design components are poorly executed, educational inequalities, stratifying students by race, class, or prior academic achievement, can be exacerbated.

Pathway AND Department Teams: While pathways need regular collaboration time to develop their teams, programs, curriculum and common assessments, many teachers also need to work in subject-specific departments, especially in areas where Common Core demands major changes in instructional practices. Negotiating the best use of professional development time, and organizing for adequate collaboration time to be able to accomplish these changes in instruction are both critical tasks for an inclusive leadership team. Involving teachers in the decision making processes facilitates collaborative problem solving and innovative approaches. This chart exemplifies the kind of organizational relationships that result.

Collaborative Time: Much research points to the critical importance of collaborative time, during which teachers can examine and refine their practice. Such collaboration can sustain continuous improvement when it is embedded in teacher communities of practice. (McLaughlin 2). Inclusive, shared leadership teams organize how time is used, ensure that adequate collaborative time is available to allow teacher pathway and department teams to meet, and provide guidance on the use of collaborative time such that it contributes to the overall, agreed-upon vision for instructional practices. This map from the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (Ann 3) is a useful tool for site leadership teams who want to grow effective, sustainable communities of practice.

1 Warner, M., Caspary, K., Arshan, N., Stites, R., Padilla, C., Park, C., . . . Adelman, N. (2015). Taking Stock of the California Linked Learning District Initiative: Sixth-Year Evaluation Report. In C. f. E. Policy (Ed.). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International.

2 McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building School-Based Teacher Learning Communities: Professional Strategies to Improve Student Achievement. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

3 Ann Jaquith, Dean, S., Snyder, J., & White, S. (2015). Mapping the Development of Conditions for Collaborative Learning in School Communities of Practice.